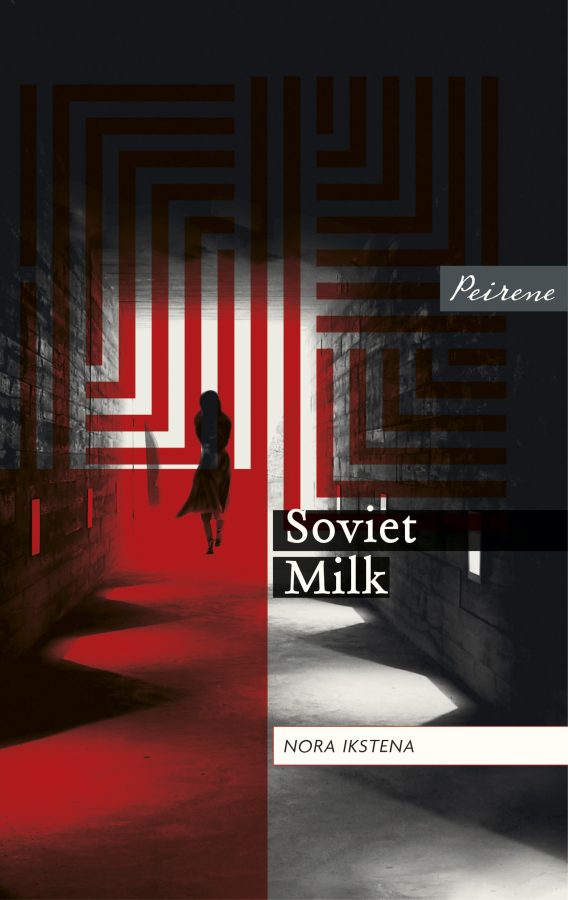

Soviet Milk

by Nora Ikstena

£12.00

The literary bestseller that took the Baltics by storm, now published in English for the first time.

This novel considers the effects of Soviet rule on a single individual. The central character in the story tries to follow her calling as a doctor, but then the state steps in. She is deprived first of her professional future, then of her identity and finally of her relationship with her daughter. Banished to a village in the Latvian countryside, her sense of isolation increases. Will she and her daughter be able to return to Riga when political change begins to stir?

Longlisted for the Republic of Consciousness Prize 2019

Shortlisted for the EBRD Literature Prize 2019

Translated from the Latvian by Margita Gailitis.

192pp, paperback, £12.00

ISBN 978-1-908670-42-7

Publication date: 1 March 2018

Press & Reviews

'A blistering Latvian bestseller... Soviet Milk powerfully evokes Latvia's bitter history.' Claire Armitstead, The Guardian

'An invaluable memoir of Latvia’s recent past...it is also one of the most devastating novels I’ve ever read about women’s lives in any society.' EBRD Prize Jury

'Soviet Milk paints a refreshingly nuanced picture of Latvia under Communist rule ... reserved, devoid of over-dramatisation, and all the more powerful for it.' Anna Aslanyan, The TLS

'This could almost be Latvia itself talking, a small, fiercely proud nation now making a literary noise outside its borders that’s long overdue.' Charlie Connelly, The New European

'Every so often, you come across a book so beautiful that you ration the pages to extend it. Nora Ikstena's Soviet Milk is most certainly one of these.' Catherine Venner, World Literature Today

'Nora Ikstena's fiction opens up new paths not only for Latvian literature in English translation but for English literature itself.' Jeremy Davis, Dalkey Archive Press

'Latvia is a country we have heard almost nothing about since its separation from the Soviet Union. Nora Ikstena is proving that Latvia is speaking in a bold and original voice.' Rosie Goldsmith, broadcaster and reviewer

About The Book

Translator

Margita Gailitis has translated some of Latvia's finest poetry and prose into English, including Sandra Kalmiete's With Dance Shoes in Sibirian Snows and Māra Zālīte’s Five Fingers. Soviet Milk is her first translation for Peirene Press.